Isn’t it time we flipped around the old ‘divide and impera’ (‘divide and conquer’) strategy attributed to the Romans and used for centuries to assert dominance? (The correct Latin term for “unite” might be “iungo”, but you get my gist). While the strategy has pretty effectively helped many generals and emperors take over large pieces of our world’s map, I am proposing that it is also the single most important reason for which most major empires have ultimately failed, being reduced to history book chapters or precious relics needing the controlled environment of museums to survive… This should not remain a history book story, but a living lesson for today’s world.

Now, fast forward to what is happening in the pharmaceutical industry today, where several companies that have dominated the world of pharmaceuticals, not unlike the great empires with their own achievements, territorial claims and peculiar corporate cultures are marching toward the “patent cliff”. The causes for what I believe is essentially a pharma innovation problem could fill in many posts. The current pharma model is increasingly more analyzed and scrutinized and thought to be unsustainable. Every day brings new stories that have created for me the vision of a pharma’s “python phase”. To feed their draining pipelines, many companies ingest and digest consecutive boluses, M&A, expansions and cuts, which constantly inflate and deflate their bodies. What I decided to do here is to simply summarize how observations I made from a completely different situation – to me, a great way to learn! – may hold clues about other powerful strategies to survive life-or-death challenges.

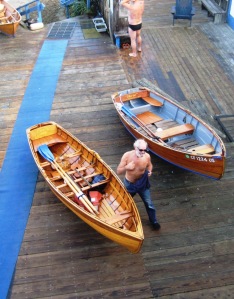

I have recently learned about the practical and harmonious solution to survive the extreme challenge of the frigid waters in the Bay area during my recent visit at the Dolphin Club, a swimming and boating club in San Francisco. I have already raved elsewhere (Sports-inspired life and business lessons“) about my admiration for its members who challenge the frigid open waters of the bay. If I had to summarize in only two points what was needed to survive those waters from an individual perspective, it would have to be: 1) cross-training and 2)… being “Zen”! But I also learned fascinating things about the strategy that constitutes the basis of the club and about its inner functioning from Reuben Hechanova, the current boat captain and upcoming 2011 president of the club. Everybody has to share learnings such as hypothermia classes and to regularly work together to maintain the wooden boats, even if they are not rowing them, as one day they may save their life. While touring the club one of the returning rowers reported to Reuben having had a “fantastic” row! “I had the opportunity to save a swimmer who was beginning to experience hypothermia”. These people not only share the waters (politely giving way), but they closely collaborate to successfully conquer them. For instance, I learned that for long swims, the club members move in a well-orchestrated formation, again reminiscent of the Roman’s tactics, with the swimmers in the middle surrounded by small boats, while all being flaked by the bigger wooden boats protecting from them from the potential impact of passing tankers and being ready to take back to safety anyone succumbing to hypothermia. In my many years as a rower, I had never come across such tight symbiotic collaboration between swimmers and boaters. I believe the reason is that I do not know of any other place that chose to deal with such an extreme challenge: normally rowing clubs have rules that require members to stop operating when the water temperature gets too low to be comfortable for swimming (to prevent hypothermia in case the rower accidentally falls into the water). Most outdoor swimming facilities close even earlier in the year! But, what is one to do in San Francisco, where the temperature of the Bay waters is never warm enough for most people to comfortably swim in it? Here, some people choose to jump into frigid waters and seem to love it, but not before having a survival strategy in place that capitalizes on the close, symbiotic, collaboration between rowers and swimmers. Rowers need to be able to withstand swimming if needed, swimmers need to be able to rely on or become rowers should one need to be saved from hypothermia.

Just had a great row... saving a swimmer!

So here are the three main points I derived from my recent visit about how collaborations may work for survival:

1. Goal/Need to conquer the same domain/major challenge, e.g., the frigid open waters.

2. Have complementary strengths: some are experts at moving inside the water, some over it.

3. Should share enough trust, knowledge, and capabilities to be able (and willing) to jump to the rescue or even into the other’s shoes, in this case, at the drop of an oar!

Also based in San Francisco is the UCSF. Last week, a press release announced a major common effort with Pfizer, which is expected to lose exclusivity for world’s largest ever earning drug, Lipitor, in exactly one year from now . The waters below that patent cliff might be very frigid indeed! We applaud this trend, it may produce some of the greatest example of ‘unite and impera’ our common global challenge: developing new therapeutics to address the unmet medical need. Let’s see, do the other, sports-inspired lessons apply? Do the two partners have different strengths? Check: academia excels at the “fuzzy” innovative front end of life science discoveries, while pharma’s strength is the late stage development and commercialization of therapies.

And, how about the third lesson: How much do pharma and academia share in terms of trust, knowledge, and capabilities? More and more facilities that are appropriate for drug development are becoming available, either “for hire”, being used by or built for academia’s and other self starters’ use. Mind you, several have been deserted specifically due to pharma’s budget cuts, including Pfizer’s own site demise in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and many are operated via new government programs. Do I dare say the major lasting dividing problem remains the lack of trust and knowledge sharing, not only of intellectual property (IP) per-se, but even that of common “know how” of drug development. A better shared understanding of “what” and “how” to develop a new medicine will only increase our common ability to conquer diseases. This knowledge, “as good as gold”, could be as enabling as the precious coins made of it, or, if not shared, will remain as elusive as the buried treasures of a lost pharma empire.